11. Markov Decision Process

Markov Decision Process

Recycling Robot Example

Let's say we have a recycling robot, as an example. The robot’s goal is to drive around its environment and pick up as many cans as possible. It has a set of states that it could be in, and a set of actions that it could take. The robot receives a reward for picking up cans; however, it can also receive a negative reward (a penalty) if it runs out of battery and get stranded.

The robot has a non-deterministic transition model (sometimes called the one-step dynamics ). This means that an action cannot guarantee to lead a robot from one state to another state. Instead, there is a probability associated with resulting in each state.

Say at an arbitrary time step t, the state of the robot's battery is high ( S_t = high ). In response, the agent decides to search for cans ( A_t = search ). In such a case, there is a 70% chance of the robot’s battery charge remaining high and a 30% chance that it will drop to low.

Let’s revisit the definition of an MDP before moving forward.

MDP Definition

A Markov Decision Process is defined by:

- A set of states: \mathcal{S} ,

- Initial state: \mathcal{s_0} ,

- A set of actions: \mathcal{A} ,

- The transition model: T(s,a,s') ,

- A set of rewards: \mathcal{R} .

The transition model is the probability of reaching a state s' from a state s by executing action a . It is often written as T(s,a,s') .

The Markov assumption states that the probability of transitioning from s to s' is only dependent on the present state, s , and not on the path taken to get to s .

One notable difference between MDPs in probabilistic path planning and MDPs in reinforcement learning, is that in path planning the robot is fully aware of all of the items listed above (state, actions, transition model, rewards). Whereas in RL, the robot was aware of its state and what actions it had available, but it was not aware of the rewards or the transition model.

Mobile Robot Example

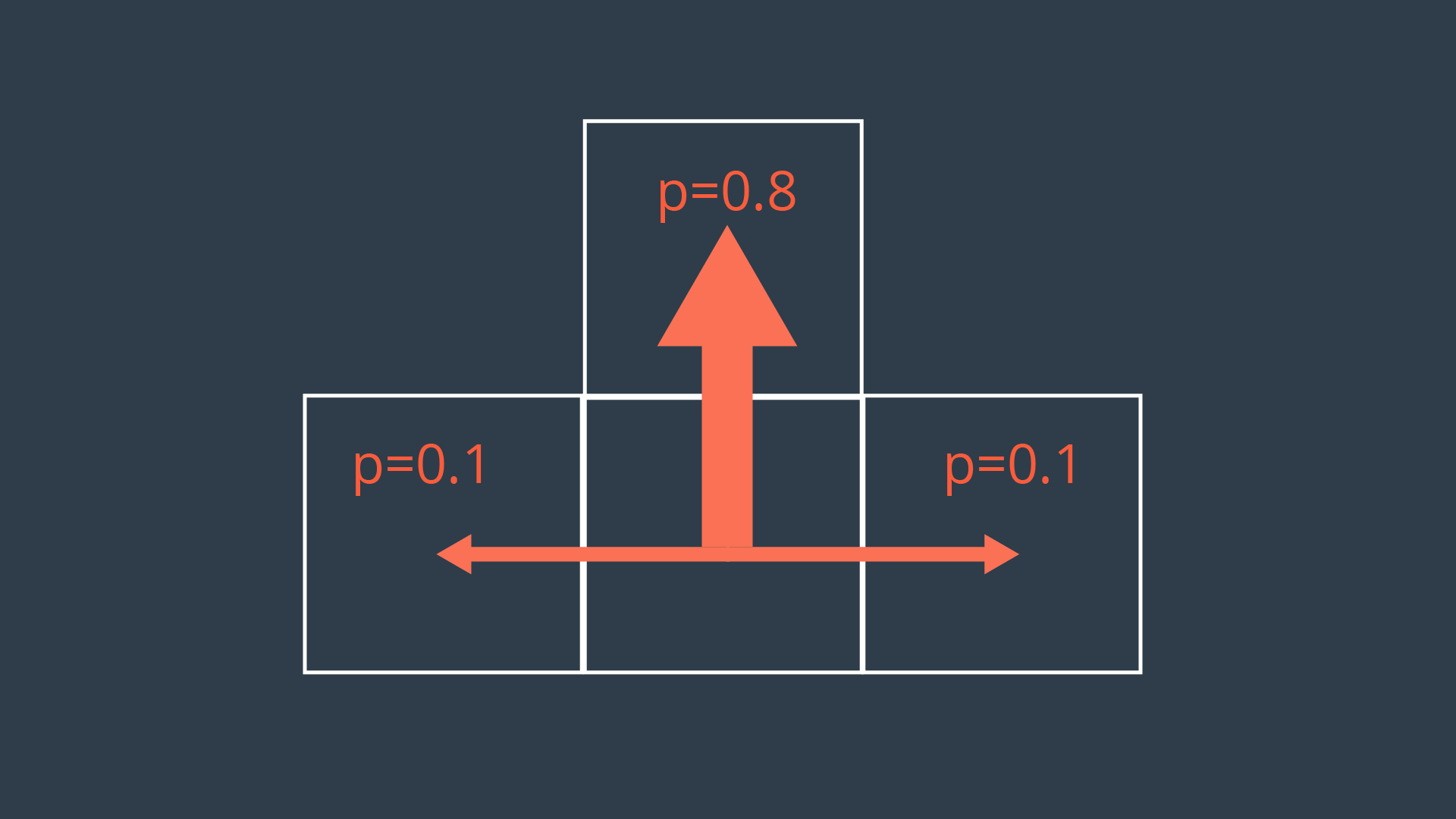

In our mobile robot example, movement actions are non-deterministic. Every action will have a probability less than 1 of being successfully executed. This can be due to a number of reasons such as wheel slip, internal errors, difficult terrain, etc. The image below showcases a possible transition model for our exploratory rover, for a scenario where it is trying to move forward one cell.

As you can see, the intended action of moving forward one cell is only executed with a probability of 0.8 (80%). With a probability of 0.1 (10%), the rover will move left, or right. Let’s also say that bumping into a wall will cause the robot to remain in its present cell.

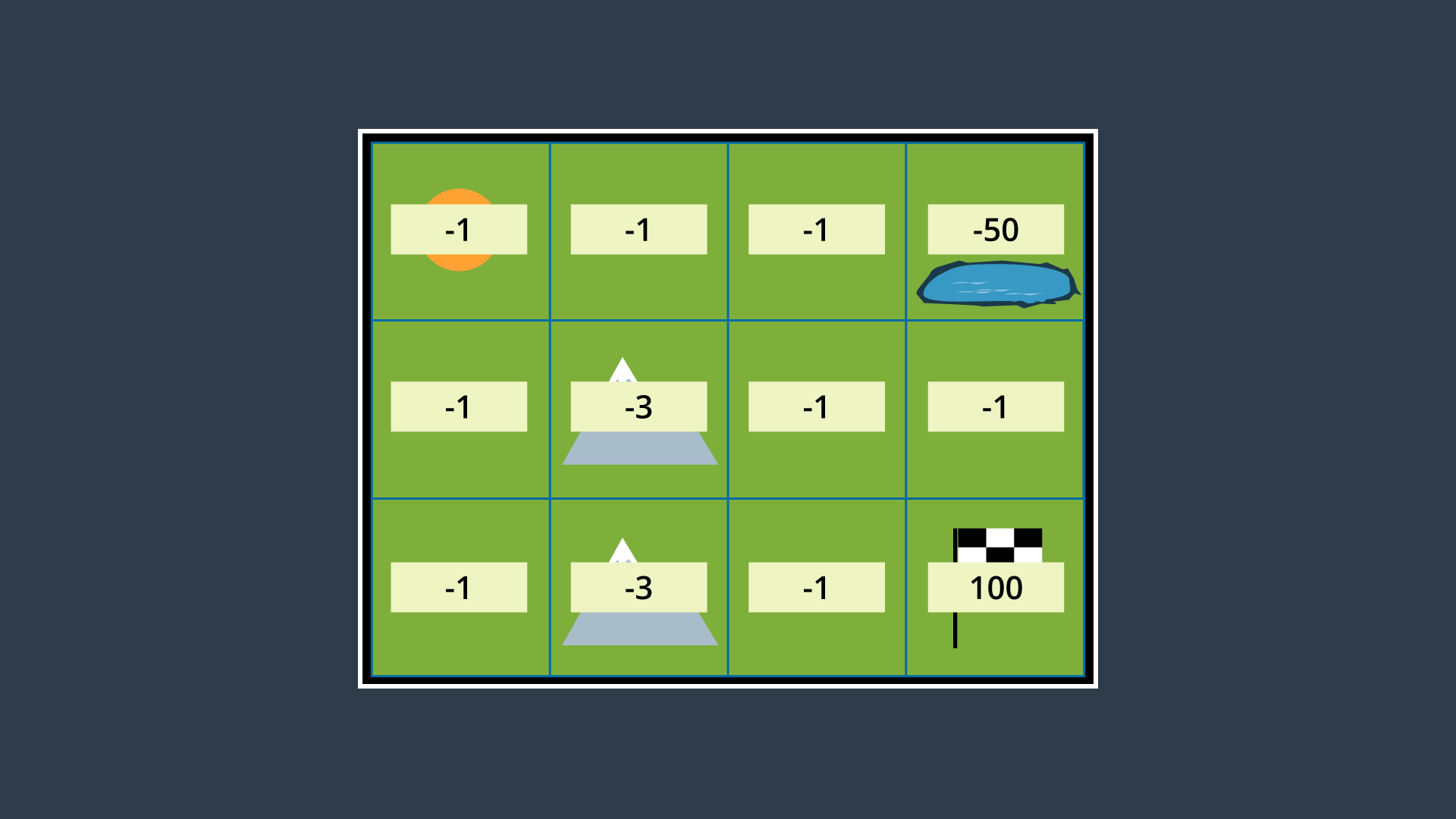

Let’s provide the rover with a simple example of an environment for it to plan a path in. The environment shown below has the robot starting in the top left cell, and the robot’s goal is in the bottom right cell. The mountains represent terrain that is more difficult to pass, while the pond is a hazard to the robot. Moving across the mountains will take the rover longer than moving on flat land, and moving into the pond may drown and short circuit the robot.

Combinatorial Path Planning Solution

If we were to apply A* search to this discretized 4-connected environment, the resultant path would have the robot move right 2 cells, then down 2 cells, and right once more to reach the goal (or R-R-D-R-D, which is an equally optimal path). This truly is the shortest path, however, it takes the robot right by a very dangerous area (the pond). There is a significant chance that the robot will end up in the pond, failing its mission.

If we are to path plan using MDPs, we might be able to get a better result!

Probabilistic Path Planning Solution

In each state (cell), the robot will receive a certain reward, R(s) . This reward could be positive or negative, but it cannot be infinite. It is common to provide the following rewards,

- small negative rewards to states that are not the goal state(s) - to represent the cost of time passing (a slow moving robot would incur a greater penalty than a speedy robot),

- large positive rewards for the goal state(s), and

- large negative rewards for hazardous states - in hopes of convincing the robot to avoid them.

These rewards will help guide the rover to a path that is efficient, but also safe - taking into account the uncertainty of the rover’s motion.

The image below displays the environment with appropriate rewards assigned.

As you can see, entering a state that is not the goal state has a reward of -1 if it is a flat-land tile, and -3 if it is a mountainous tile. The hazardous pond has a reward of -50, and the goal has a reward of 100.

With the robot’s transition model identified and appropriate rewards assigned to all areas of the environment, we can now construct a policy. Read on to see how that’s done in probabilistic path planning!